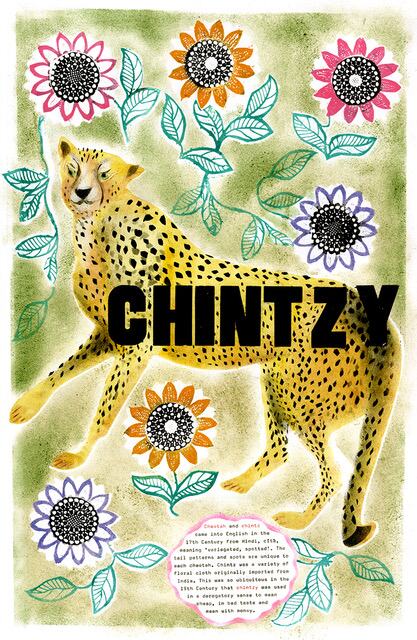

Serendipity by Mary Kuper

I wanted to illustrate the word ‘serendipity’ because it encloses a complete fairy tale.

In 1302 Amir Kushrow, Sufi mystic, poet and musician wrote a poem about the Three Princes of Seredip, the old Persian name for Sri Lanka. Their father the king, satisfied with their fine education, offered the kingdom to each prince in turn. They refused it, claiming to be less fit to rule than their king who then sent them off to make their way in the world.

In 1754 the English writer and statesman, Horace Walpole, was inspired by their story to coin the word ‘serendipity’ to describe the way the princes were ‘always making discoveries, by accident and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of.’ (H. Walpole)

In one story the princes help to search for a lost camel. They tell the owner that the camel is lame, blind in one eye and ridden buy a pregnant woman. It carries honey on one side, butter on the other. The description was so accurate that they were accused of theft until they explained how they knew so much. The grass was cropped short on the less fertile side of the road so the camel must be blind on the other side. Only the tracks of three feet were crisp, so the animal must be lame and missing a tooth because grass clumps, the size of a camel’s tooth, were lying on the road.

They guessed the load was honey and butter by the flies and ants on opposite sides of the road, as honey attracts flies while ants like butter. The rider had to be a woman because they reacted with lust to her traces in the sand where the camel had knelt down. They knew she was pregnant by handprints showing she struggled to get up again.

Their evidence so impressed the emperor that he made the princes his advisors. It also inspired the word ‘serendipity’ for discoveries ‘made by chance, found without looking for them but possible only through a sharp vision and sagacity and never indulgent with the apparently inexplainable.’ (H. Walpole)